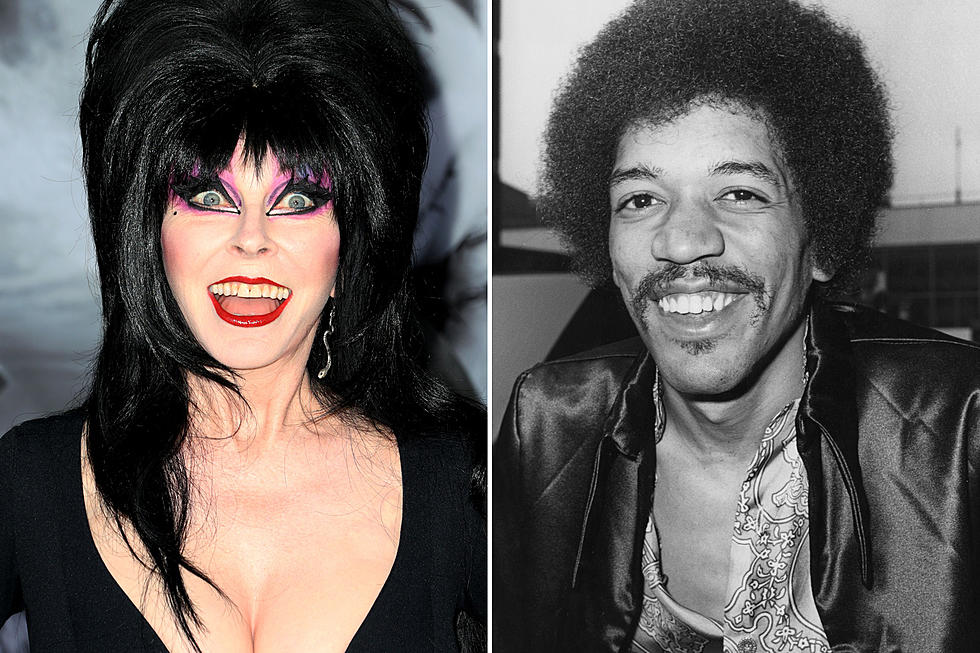

Elvira Recalls Tear Gas Attack That Led to Jimi Hendrix Kiss

When cops launched a tear gas attack on the Denver Pop Festival audience in 1968, it inadvertently led Cassandra Paterson into the arms of Jimi Hendrix.

Peterson – who later found fame as horror comedy character Elvira, Mistress of the Dark – had only graduated from high school when she and her friend Cindy decided to try for some groupie experience in and around the Mile High Stadium, where Hendrix was to play along with Frank Zappa, Joe Cocker, Johnny Winter, Creedence Clearwater Revival and others.

“We didn’t bother to get a motel because we figured we’d be up all night in the room of some band or other,” Peterson wrote in her recent memoir Yours Cruelly, Elvira. “All we brought along were our toothbrushes, a change of underwear, makeup and false eyelashes, a few joints, and a lot of eau de cologne.” She recalled wandering from “hotel room after hotel room” until she spent the first night of the festival with “the drummer from Three Dog Night” – only to be “unceremoniously kicked out sometime in the wee hours of Saturday morning when I refused to put out.” She found her way to where Zappa was hanging out, and “sat on the floor with my mouth hanging open in awe, thrilled to be in the presence of such greatness.” She recalled: “Frank Zappa, the only person in the room who didn’t seem high, told me in a fatherly way that I was too young to be wandering around the hotel on my own. I paid no attention to him, of course, but I thought it was very sweet of him to be concerned.”

The following day, Peterson and Cindy pushed their way to the front of the festival arena, determined to be in the best location for Hendrix’s show. There was a strong police presence as a result of violence the previous evening, which caused a raising of tension during the long wait for Hendrix. Eventually, she wrote, the crowd rushed the stage and the cops retaliated without reservation. “[They] began lobbing canisters of tear gas into the crowd. Pandemonium ensued. … A voice over the PA system kept yelling, ‘Cover your face! Cover your face!’ Suddenly, I felt a sharp whack on the side of my head, and everything went black. When I woke up, dazed and confused, I was in a trailer behind the stadium with a medic leaning over me. My head was throbbing and the side of my face felt like it was on fire. ‘Where am I?’ I whimpered. ‘What happened?’ ‘Looks like you got hit with a tear gas canister,’ the medic replied, matter-of-factly. ‘You’ve got a little cut on your scalp and some chemical burns on the side of your face, but don't worry, you’ll be fine.’ Easy for you to say, Mister. I might be missing Jimi Hendrix!”

Peterson’s fortunes began to change as she left the medical trailer. “I passed another small motor home where a very large man with a gigantic Afro stood guarding the door. Arms folded, looking a lot like the genie from Aladdin’s lamp, he called, ‘Wanna meet Jimi Hendrix?’ I couldn’t believe my ears.” Admitting it was a “gullible” move, she followed the crewman into the trailer – but it was true: Hendrix was there, “half lying on a convertible bed in the back of the trailer.”

He asked her what was going on in the arena, and she offered a full account. Seeing her injuries he took a damped towel and cleaned them up, before lighting a doobie. “We lounged on the bed and smoked it while he launched into an angry diatribe about the pigs, America, Vietnam, and ‘the system,’” she recalled. “I listened and nodded enthusiastically in agreement. Even though he was as pissed off as could be, I was struck by the fact that his voice still remained soft, deep, and even. No shouting or yelling… he was telling me he’d had it with the US and was going to leave the country for good.” At that moment he was told it was time to hit the stage. “Jimi scribbled a phone number on a scrap of paper and stuffed it into my hand. ‘Call me after the show,’ he said. As he made his way to the door, he stopped, wrapped his arms around me and kissed me so sweet and slow that I thought I’d pass out.”

Peterson couldn’t know at the time that she was watching the final performance of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, who split up that night. But she had half her mind on the possibilities connected with making the phone call. When she did, it wasn’t what she’d hoped for. “[S]omeone answered! It was a girl. My heart sank. This was definitely not in the plans. I could hear loud music and what sounded like a party going on in the background. ‘Is Jimi there?’ I asked, trying not to sound as disappointed as I was. ‘Whosis?’ she slurred. ‘Tell him it’s Cassandra.’ I heard her yell Jimi’s name a couple of times, then I waited for what seemed like an eternity. ‘Wh000ttrrrrrr shugumm uh huh rrrgggh.’ It was Jimi’s voice. ‘Jimi, Jimi! Hi! It’s me, Cassandra! Remember? The girl you met backstage?’” That’s all the sense she got from him until he finally dropped the handset on the floor. “I stayed on the line for a minute listening to the sounds of partying, tears welling up in my eyes. Finally, I put the receiver back on its cradle. As if I wasn’t already bummed enough, Cindy was so angry that I hadn’t asked him where he was staying that she refused to speak to me. All this made for a long, silent drive back to Colorado Springs.”

Reflecting on her groupie era, Peterson, now 70, admitted it had caused issues with her parents, but noted: “For all my crazy prick-teasing behavior, I never found myself in any serious trouble while chasing bands. I got thrown out of a room or two when I wouldn’t put out, but I was lucky. It was definitely a more innocent time. Hippies were preaching ‘peace not war,’ love-ins and flower power abounded, and young people were sure they were going to save the world. Life in the ‘60s, for the counterculture – of which music was a centerpiece – was all about beauty, honesty, and fun; but most of all, love.”

Top 100 '60s Rock Albums

More From